How do privacy laws protect us?

Privacy boils down to knowledge and agency. Data knowledge is who has information about you: who you are, where you live, and what your online activities are. Agency is the ability to control this information—deciding who else can see your data, and for what reasons.

An example: If you visit an article about National Parks in the New York Times, you know that the Times now has some information about your interests (parks!). However, you might not know that an ad network that works with the Times now also knows this about you, and will use this knowledge to serve you ads about National Parks when you visit Facebook or watch videos on Youtube. This is what we mean about knowledge: being aware of all the entities that learn stuff about us.

Being able to tell the ad network: “hey, forget that I ever visited this site” (so they stop serving me ads about National Parks) is what we mean by agency: being able to control this information other entities have about us.

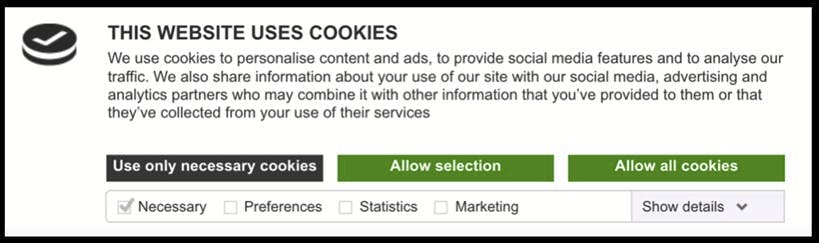

That’s why privacy laws require organizations to inform consumers of what information is being collected about us, how it’s being used, and for what purposes. Cookie banners, which we see on almost every website, are designed in response to laws requiring customer agency about data. With banners like this, we can opt-in or opt-out of providing our information to organizations.

Here’s what most privacy laws address in general (we’ll get into localized laws in a minute):

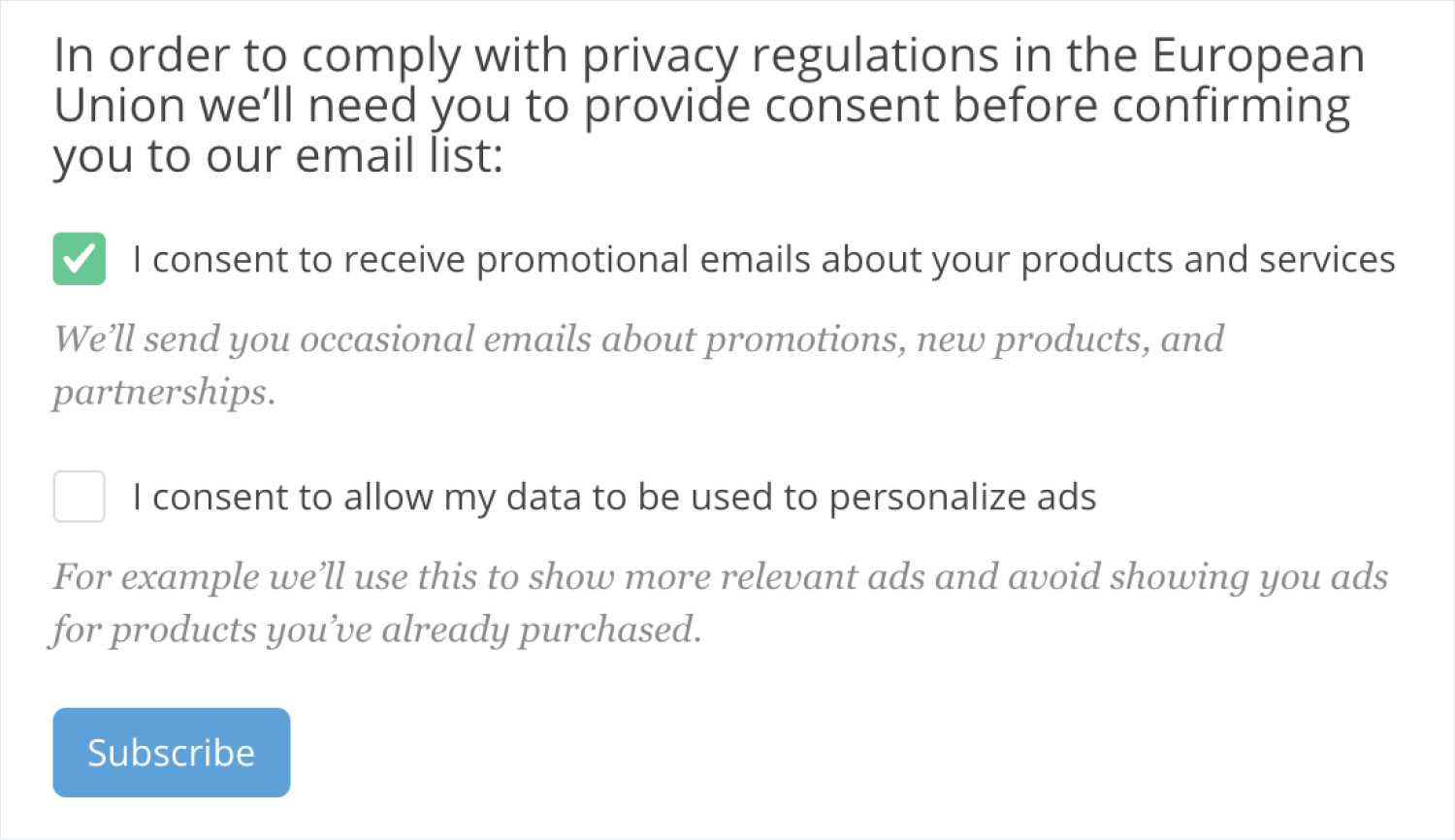

Can your information be collected in the first place: Sometimes privacy laws require organizations to get consent to access and collect data. In some cases, the consent must be obtained by asking the consumer directly (usually called opt-in), and in others, consent may be implied but there must be ways by which the consumer can opt-out. This usually shows up in the form of popups on websites and apps where we can choose to allow or deny consent, like this one:

Require organizations to show us the data they have about us if/when we ask them to: Data access is one of the most common rights established in privacy laws. Websites and apps can be required to have a form, email, or telephone number where consumers can request a copy of all the information the organization has about them. Sounds scary? Try it, and see what information you can find. Here’s how to request your Facebook data, for starters. In some cases, the amount of information is so much that it’s necessary to use analysis tools or have the skills to sift through large amounts of data, which is usually not within the average consumer’s reach. (No offense to the average consumer.)

Require organizations to delete our data if/when we ask them to: Another common requirement set by privacy law is the right to request the deletion of all information linked to us. This is usually accessible to consumers through similar methods as the access request, via web forms, or by contacting the organization directly.

Deleting your information doesn’t mean going off-the-grid, or even quitting social media. If we go back to the example of visiting a National Parks article in an online newspaper, we may not mind having the NYT know our reading preferences, but we might not want that information to spread to other companies. If this is your case, then you might tell the main ad networks and data brokers to delete your data from their systems. These companies are specifically in the business of compiling profiles about us and selling them, which leads to the further spread of our information beyond our knowledge. You can read more about erasing your personal data in this Vox article.

Require organizations to update or correct our data if/when we ask them to: Data is increasingly used and interpreted directly by machines, algorithms, or automated rule systems that don’t have the ability to contextualize it or identify obvious mistakes. Because of this, incorrect information can cause issues such as impairing a consumer’s credit score, driving up the cost of insurance, or simply providing incorrect product recommendations. On the plus side, some (emphasis on “some”) privacy laws require companies to update data in a timely manner, mostly when identified and required by the user. This way, incorrect information can’t be used against you.

So...what privacy laws are out there for me?

Depending on where you live, privacy laws may have different levels of strictness (and trickiness). Here are some of the most common privacy laws based on location:

European Union

Internationally, one of the most common privacy laws right now is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (or GDPR). This law came into effect in May 2018. At a high level, this law addresses three main topics that protect consumers’ data:

1. When and how to collect consent

2. Our rights as consumers (these are all the ones we just covered about access, delete, and update as well as some additional ones), and

3. A set of controls organizations must put in place to protect and safeguard our data (and the potential fines and penalties for failing to comply).

Brazil

In Brazil, the Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais (or LGPD) came into effect in August/September of 2020. Its impact on consumers is very similar to the GDPR, except that it adds to the list of allowed purposes for which providers can use personal data without the individual’s explicit consent: research studies, and protecting credit scores.

Canada

Canada has two older privacy laws: the Privacy Act from 1983 (which regulates how institutions within the Government of Canada have to manage personal information) and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (or PIPEDA) from 2001 that gives individuals most of the rights mentioned above, and requires organizations to obtain consent for processing consumer’s personal information.

The Canadian government has been working on a new privacy law: Canada’s Consumer Privacy Protection Act (or CPPA). If this law is adopted, one of the main highlights it would provide us with is a more comprehensive set of rights for consumers (similar to GDPR and LGPD)—in particular regarding deletion and the right to withdraw consent.

United States

The US has no single federal law that addresses privacy for all types of information. However, there does exist a collection of pieces of legislation that play a role in this. Some legislation is at the federal level; some exist only in specific states.

Federally, there are several laws that address privacy of personal information for specific industries and contexts. In particular:

- Financial Information: Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999. Requires financial institutions to inform consumers of the information collected, its use, and how it’s being shared.

- Health Information: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Gives consumers the right to access their personal health information and establishes a set of required security protections for safeguarding this information.

- Information about children: Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998. Establishes a set of required safeguards for online services that collect information about children under 13 years of age.

Another high-profile, highly enforced piece of legislation is the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act of 1914. Although it doesn’t address the protection of privacy explicitly, Section 5 establishes as unlawful “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.” The FTC has fined companies from Cambridge Analytica to Equifax’s data breach for failing to meet their own promises of safeguarding their users' data.

In recent years, there have been a series of efforts to bring more comprehensive privacy laws to the state level. The most well-known of these are the laws brought forth by the state of California in the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) and the subsequent California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA). These laws further extended consumer’s rights by adding the right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information to third parties. Look up privacy laws near you by looking up IAPP’s state privacy law tracker.

What can you do?

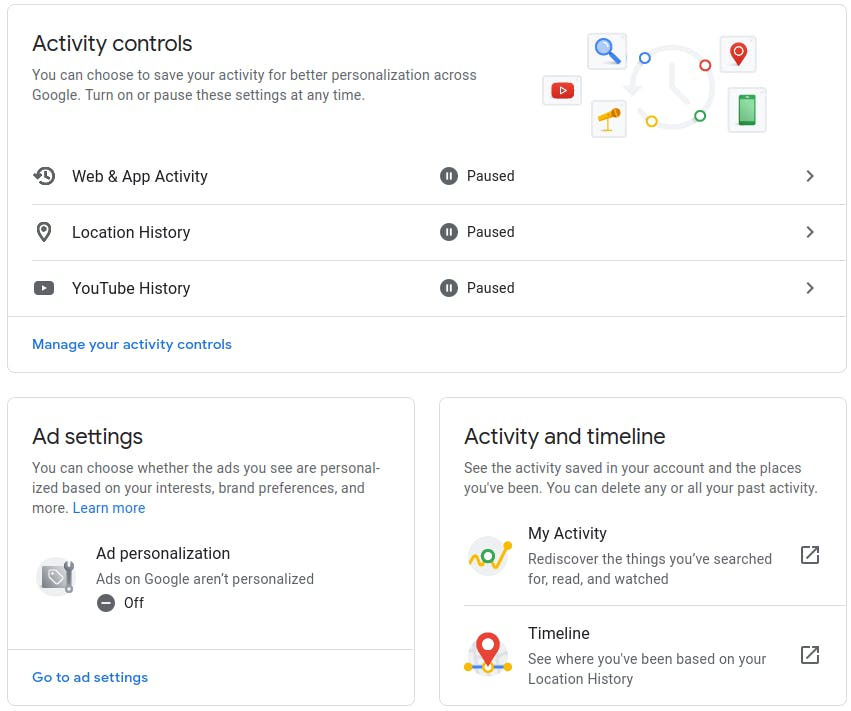

Hopefully, you’ve taken away that privacy laws are much more than just annoying cookie banners all over the web. You can always use overviews like this one to your advantage rather than reading through pages of dry, legal, privacy policies. Or, poke through your accounts and see what information you can find about your data. A great way to get started is to visit Google’s Data and Personalization dashboard for your account.

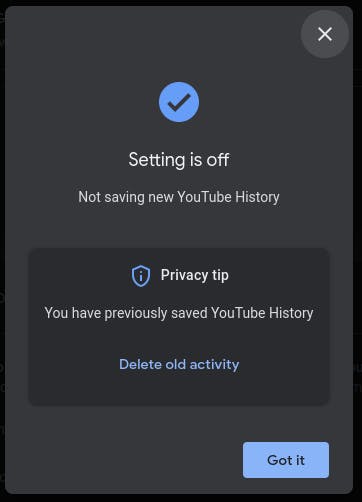

Although Google (and most other tech companies) still has much to improve with regards to their privacy practices, their dashboard tries to make it easy for users to explore the data they have about you (like search history, or location history), as well as turn on and off tracking of certain types of information like web activity, youtube history, location tracking, and ad personalization. Again, the important thing is that you get to choose what type of information is okay for them to have about you, and what information should be forgotten and deleted forever. Try it out with Google, your social media accounts, or even read a little more closely the next time you see a cookies banner. After all, they’re only there to help.

What do you want to know about data, privacy, or technology?

Data Curious is a public resource supported by Good Research LLC in collaboration with the Center for Digital Civil Society at University of San Diego.

To contact us, send us an email at hello@datacurious.org.